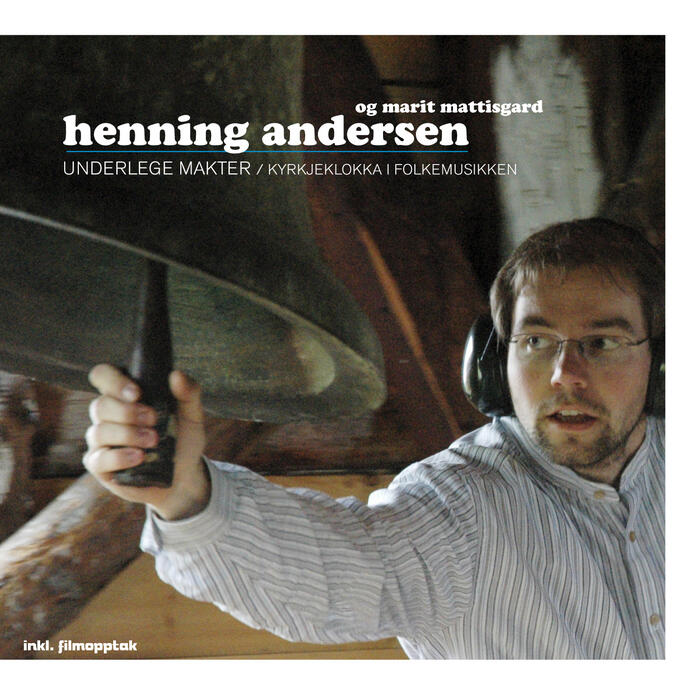

Underlege makter

I uminnelege tider har kyrkjeklokkene kalla folk saman til høgtid og fest, til sorg og til glede. Kyrkjeklokkene har vore eit sikkert og trygt landemerke for folk her i landet i godt og vel tusen år. Dei har opp gjennom åra hatt ulike oppgåver, men fyrst og fremst har dei vore Guds røyst til menneska her på jorda. Kyrkjeklokkene har kalla folk saman til messe og kyrkjelege handlingar, men dei fekk og etterkvart fleire viktige oppgåver, ikkje berre kyrkjelege, men og verdslege. Kyrkjeklokkene vart nytta til å varsle krig og til mobilisering. Dei vart nytta til å varsle ulukker og katastrofar. Dei varsla tidene på døgnet, arbeidsdagen sin start og slutt, og dei varsla at helga byrja og slitne kroppar kunne få kvile.

Her i Valdres har kyrkjeklokkene ringt i snart tusen år, og me kan vel ikkje tenkje oss ei kyrkje utan kyrkjeklokker. Me tenkjer oss attende til 1000-talet då dei fyrste kyrkjene her i Valdres vart bygd. Tenkjer på kva inntrykk det gjorde på Valdrisen då dei fyrste store kyrkjebygga stod klare og kyrkjeklokkene kima utover bygdene. Dette var både eit syn og ein lyd dei aldri før hadde vore vitne til. Klangen frå klokkene verka kan hende skremmande i fyrste omgang. Den var underleg, den var skummel, den var kraftig, den var ny og ukjent. Kyrkjeklokkene representerte Gud. Det var Guds stemme som tala til folk. Det var difor kyrkjeklokkene vart tillagt så stor tyding og magiske eigenskapar. Og me kan kanskje i same andedrag seia at av alle dei skikkar som kristendomen førte med seg så er det vel få som gjorde eit så sterkt inntrykk som ringing med klokker. Difor meinte dei gamle at når kristendomen vant fram her i nord, så var det skuld i at den vart ringt inn i sinna på folk.

Klokkene blir til

Me kan på mange måtar seia at klokkestøypinga si vogge stod i Asia. Herifrå har spreiinga av klokkene til Europa og særleg Norden gått føre seg via fleire vegar. Særleg tre vegar utmerker seg. Keltarane var godt kjende som svært gode bronsestøyparar, og dei har fått med seg klokkene til England, Skottland og Irland. Derifrå har dei vorte med vikingane til Norden, kanskje alt så tidleg som då klosteret i Lindisfarne vart plyndra av norske vikingar i 793. Ein almen spreiingsveg er frå Asia, over Svartehavet, gjennom Russland og så opp til Norden. Men ein tredje veg har fått mykje å seia for den kristne kyrkje sin bruk av klokkene. Den vegen går frå Asia, over til Nord-Afrika og derifrå til Italia. Me har nemleg belegg for at dei fyrste kyrkjeklokkene vart innført frå Karthago til Italia i år 535. (Karthago, handelsby i oldtida på nordkysten av Afrika, i nærleiken av Tunis.) Det er i katakombar og kloster me fyrst finn kristen bruk av kyrkjeklokker. Den eldste, støypte bronseklokke me har i dag er berre 8 cm høg og har ei sylindrisk form. Denne klokka vart grave fram i Ninive (det gamle Assyrias hovudstad ved austbreidda av Tigris) og alderen er vorte fastsett til om lag 3000 år. Sjølv om det her er skissert fleire spreiingsvegar for klokkene til Norden, er det likevel biskop Ansgar (Nordens apostel) som har fått æra av å ha innført kyrkjeklokka til Norden. Det skal ha skjedd i 830. På byrjinga av 700-talet fekk ein små klokketårn til å henge klokkene i, dei såkalla ”kampaniler” av lat. campana, klokke jfr. vår klokkestupul. Opp gjennom tusenåra har klokkene smått og forsiktig endra seg fram mot den klokka me kjenner i dag. Klokkene blir laga av ei legering av kring 22% tinn og 78 % kopar. Det er i all hovudsak same legering som for 5000 år sidan. Men det har likevel vore eksperimentert mykje med form og fasong. Den klokka me kjenner i dag fekk i hovudsak sin form mot slutten av 1400-talet, og den blir kalla for den harmoniske klokke. Det var klokkestøypar Gerhard van Wou som er mannen bak denne klokkeprofilen, og enno finst mange av klokkene han støypte. Den største av dei alle er klokka Gloriosa som heng i Mariakyrkja i Erfurt. Klokka veg kring 11 tonn og er støypt i 1492.

Den særmerkte klangen I det bellen (kolven) råkar slagringen på klokka høyrer ein ikkje berre ein einskild tone, men eit heilt arsenal av tonar. Og det er dette som blir kalla naturtonerekkja/partialtonerekkja. Den fyrste tonen ein høyrer er slagtonen og underoktaven. Så overoktaven, molltersen, durtersen og så overoktaven. Deretter ligg tonane tettare og tettare, men nesten ikkje mogleg å oppfatte av det menneskelege øyra. Det er samansetjinga av desse tonane som gjev klokkene den karakteristiske og særmerkte klangen. Korleis desse tonane kjem og kor sterke og reine dei einskilde blir, er avhengig av legeringa på klokkebronsen og på profilen klokka har fått. På byrjinga av 1600-talet fant brørne François og Pieter Hemony frå Lotharingen i Nederland ut at det gjekk an å stemme klokkene. Dei dreia av metall frå innsida av lokka slik at dei ulike overtonane fekk rett høgd. Måten å stemme klokker på i dag er i all hovudsak sama måten som Hemnoy-brørne nytta for snart 400 år sidan. Klokkeringing er her i landet ein nesten 1000 års ubroten og levande tradisjon. Det er ein tradisjon me lyt vera stolte av. Kunsten å ringje med klokker har vorte overlevert på gamlemåten, altså gjennom læremeister til elev. Å ringje godt med kyrkjeklokker er ein kunst ein ikkje lærer over natta. Det er nemleg ikkje så enkelt som å dra i klokketauget og håpe på lyd. Det trengst lang trening for å få klokkene til å ringje fint. Få dei til å gå med den rette farten, å få slaga til å bli så harde at klangen høyrest langt, samstundes som klangen skal vere så mjuk og fin som mogleg. Om det er vanskeleg å ringje ei klokke blir det ikkje likare når ein skal ringje to eller fleire klokker. Men det er samstundes då det blir meir moro. Moro når ein får til gode klangfargar mellom tonane i klokkene, og når ein får ei god rytme i ringinga. Det er ikkje sjeldan at kyrkjeklokkene i Aurdal har kalla kyrkjelyden til gudsteneste syndag morgon i springartakt! For å få til dette lyt klokkene ringjast på gamle måten, altså med handkraft. Spelemannen Ola på Hamrisbrøto var og ringjar i Slidredomen. Han hadde ein gong laga ein tjærekross i ein av takåsane i stupulen i Slidre. Den synte kor høgt han ville ha klokkene til å ringje. Krossen er synleg den dag og blir av nokre kalla for ”spelemannskrøssen”. Spelemannen og folketalaren Olav Moe har skrive dette om Ola på Hamrisbrøto: "På sine gamle dagar vart Ola dørvaktar i Slidredomen, og når dei herlege kyrkjeklokkone ikkje gav den samljod under ringingi, som han tykte dei skulle ha, kunne ein sjå ein sår grin over andletet på kyrkjetenaren. Det var det vakne, harmoniske musikkglimt i sjeli hans som var såra" Olav Moe

Klokker i tårn, stupul eller klokkespel

Det er i dag mange måtar å henge klokkene opp på, anten i kyrkjetårnet, i stupulen (frittståande klokketårn) eller i eit klokkespel. Dei fyrste og eldste klokkene me kjenner til har i all hovudsak vore nytta som signalinstrument. Så då kyrkja tok i bruk klokkene, var det som eit varslingsinstrument, dei skulle kalle folk saman til messe. Dette var helst mindre klokker som vart frakta med seg av den som hadde som oppgåve å samle folket. Etter kvart vart klokkene større og tyngre, og vanskeleg å frakte rundt. Då vart det bygd klokketårn der klokkene kunne henge. Seinare vart det og bygd tårn på kyrkjene der klokkene kunne henge. I Valdres har me framleis tradisjonen med klokker både i kyrkjetårnet og i eige klokketårn, eller stupul, som me seier i Valdres. Opp etter hundreåra kom og tanken om å nytta klokkene til å spela melodiar på, og dei fyrste primitive klokkespela dukka opp. Frå slutten av 1500-talet og godt innpå 1600-talet fekk me så i grove trekk dei klokkespela me kjenner i dag. Klokkespela blir etablert som eit symbol på økonomisk velferd, og det var særleg byane i Flandern som hadde økonomisk framgang innan handel og industri på 1400- og 1500-talet, og det var her ein seier at klokkespelet si vogge stod. Kring i verda finst det i dag nærare 600 konsertklokkespel, og 9 av dei har me i Noreg. For at klokkespel kan kallast eit konsertklokkespel lyt det ha minst 25 klokker (to oktavar) og vera knytt til eit klaviatur.

Klokkelåttane

Som nemnt hadde kyrkjeklokkene ei underleg makt over folkehugen i gamal tid. Så snart dei høyrde klokkeômen, stana dei opp i arbeidet sitt, strauk luva av og lydde. Klokkeklangen kunne jamvel få alt slags trollskap i haug og hamrar til å bli til stein. Då dei fyrste kyrkjene vart bygd her i Valdres frå 1000-talet og utover representerte dei noko heilt nytt og framandt for folket. Kyrkjebygga var større enn nokon andre bygg dei før hadde sett. Dei var rikt utsmykka med utskjeringar og flotte måleri. Bilete av englar og gullbelagte madonna’ar. Ikkje minst hadde desse svære kyrkjebygningane kyrkjeklokker som gav frå seg ein nesten skummel og svært høg lyd. Ikkje sjeldan hadde kyrkjene fleire klokker. Då desse klokkene ringde samstundes var det ikkje vanskeleg å skjøne at valdrisane vart ærbødige og andektige. Messa dei feira i kyrkjene denne tida gjekk føre seg på latin, og var uforståeleg for dei fleste. Messesongen forstod dei ikkje noko av, men dei lærde seg melodiane og tok dei med seg heim og dikta nye tekstar til. Likeins har klangen og dei enkle melodiane frå klokkene inspirert folk til å lage melodiar, det me i Valdres kallar klokkelåttar. Klokkelåttane ilag med salmetonane frå messa har vore element folk tok med seg heim og nytta til sine private messer, tidebøner og husandakter og elles som hjelp og trøst i vanskelege situasjonar i kvardagen. Sjølv om klokkelåttane fekk svært så verdslege tekstar etterkvar, hadde i alle fall dei små melodiane snev av noko kristeleg i seg. Klokkelåttane har sjeldan eller nesten aldri noko særleg kyrkjeleg eller kristelege element i seg. Dei hentar som regel ord og vendingar frå daglegtale. Andre gonger har dei fått små historier knytt til seg, eller dei rett og slett berre har fått lydmælande ord, som: Ding dang. Dalang…… . Nokre gonger har klokkene fått tillagt ein refsande peikefinger. Som før nemnt så meinte mange at klokkene var Guds stemme. Og ikkje underleg var det at Gud sjølv tala og mana folk til å leva rett. Kyrkjeklokkene i Slidredomen i Vestre Slidre har ofte ein lei tendens til å røpe at nokon kjem for seint til kyrkja, som til dømes: seint koma sjeladn, seint koma beitingadn.” (Skjel og Beito er to bygder i Øystre Slidre, som i gamal tid båe høyrde til Slidredomen.). Ein gong den eine av kyrkjeklokkene i Slidredomen vart stolne var det dei andre klokkene som ringde og vekte presten. Klokkene fortalde då kven som hadde stole klokka og kor dei skulle finne henne att, og til sist kor tjuvane låg. ”Kome nord” klukkelåtten frå Vang er vel kan hende den einaste av klokkelåttane våre som har eit lite snev av kristelege element i seg. Klokkene syng om å ”fara varleg, vandra sparleg. Vegen e so farleg.” Kan dette ha noko med Preikaren (forkynnaren) 4, 17 å gjera tru? - ”Akta foten din når du går til Guds hus!”

Kvifor så mange klokkelåttar i Valdres?

Tradisjonen med klokkelåttar finn me ingen andre stader i landet enn i Valdres. Kva grunnen kan vera til det er vanskeleg å seia, men har likevel prøva meg på eit par vage forklaringar her: I Valdres har me i dag godt 30 kyrkjer og i overkant av 60 kyrkjeklokker. I mellomalderen var talet på kyrkjer omtrent det same, men talet på klokker var mykje høgre. Ved kvar kyrkje var det ifrå 2 til gjerne 6 klokker. Med så mange kyrkjeklokker som ringde til alle tider og alle stader måtte det ha vore nesten som ein evig klokkeõm her i Valdres i gamle dagar. Og då er det kan hende ikkje så rart at me har fått så mange klokkelåttar som me har. Kan forma på dalen ha noko å seia for korleis klangen frå kyrkjeklokkene blir? Vatnet i dalbotn og så fjella på kvar side av dalen, kan det ha noko å seia for klangen klokkene får? Då dei i Lomen sokn i Vestre Slidre skulle få seg ny kyrkje rett etter førre århudreskifte vart det vedteke at dei gamle kyrkjeklokkene skulle flyttast frå stupulen ved den gamle Lomiskyrkja og over til den nye som låg litt lengre nord og ned i bygda. Klokkene vart flytte men hadde ikkje ein så fin klang der som ved gamlekyrkja. Nokre år seinare, då dei hadde fått råd til nye klokker, vart dei gamle flytt attende til sin opphavlege plass, og dei song like så fint som dei aldri har gjort før. Det vart då gissa på at det var Lomisberget rett bak kyrkja, som var med å laga den rette ”atmosfæren” for klokkene. Kan me utifrå dette dra ein konklusjon om at Valdres er som skapt for kyrkjeklokker? Klokkeõmen frå farne tider I tusen år har kyrkjeklokkene kalla oss til kyrkje, i sorg og i glede. Og sikkert kjem dei til å ringje i generasjonar etter oss. På same måten som mange av dei nesten 1000 år gamle klokkene her i Valdres ringde for dei som fekk høyre dei som nye, har dei ringt for generasjonane etter, heilt fram til at dei i dag ringjer for oss. Slik kan ein seia at kyrkjeklokkene ikkje berre ringjer for dei som ein messesyndag har funne vegen til kyrkja, men dei ringjer for alle, anten dei sit heime, arbeidar ute i hagen eller på jordet, eller går ein syndagstur. Dei ringjer og for dei som har vandra her før oss, og som no kviler på kyrkjegarden.

/ Henning Andersen

The bells ring

From time immemorial the church bells have rung in to festival and feat, to sorrow and joy. For people here in Norway the church bells have been a sound and safe landmark for over a thousand years. Over the years they have served various purposes but primarily have been God’s voice here on earth. They have summoned the congregation to church service, baptisms, confirmations, weddings and funerals. Gradually they gained other duties than the sacral as they were used to warn of war and mobilisation, accidents and catastrophes. The bells marked the passing hours, the start and end of the working day and the commencement of church holidays when tired bodies could rest.

Here in Valdres church bells have rung for nearly a thousand years and we can hardly conceive a church without them. If we think back to when the first churches were built in the valley, we can try to imagine the impression they made on the inhabitants when they were finished and the bells rang out over the countryside. Both the sight and sound had never been experienced there before. Perhaps at first the bells sounded menacing. It was strange, frightening, powerful and alien. The church bells represented God. They were God’s voice that spoke to the people. That is why they were allotted such significance and magic powers. And in the same breath that of all the customs which Christianity brought with it there are few that made such an impact as the ringing of bells. That is why in ancient times old folks claimed that Christianity triumphed in the north because it was rung into the minds of the people.

The bells are cast In many ways we can say that the cradle of bell casting was in Asia. From there to Europe and to the Nordic lands especially bells spread along several routes. Three routes in particular stand out. We know that the Celts were famed for their skill in casting in bronze and brought bells with them to the British Isles. From there the Vikings brought bells to Scandinavia, maybe as early as the plundering of the convent at Lindisfarne in 793. A general route for the spread of bells is from Asia across the Black Sea through Russia and then up to Scandinavia. However, a third route has had a considerable influence on the Christian church’s use of bells. This route went from Asia to Italy via North Africa. There is evidence to support the claim that the first church bells were taken from Carthage to Italy in 535 (Carthage, ancient trading port on the north coast of Africa near Tunis). It is in the catacombs/ convents that we find the first Christian use of bells. The oldest preserved cast bronze bell we have today is only 8cm high and has a cylindrical shape. This bell was excavated in Nineveh (the ancient Assyrian capital on the east bank of the Tigris). It has been ascertained to be around 3000 years old. Even if several routes have been sketched in for the spread of bells to Scandinavia, it is nevertheless Bishop Ansgar (the Apostle of the North) who has received the honour of having introduced church bells to the region. It is supposed to have occurred in 830. At the beginning of the eighth century they began to build bell tower, so-called campaniles from the Latin for bell “campana”. It is also from this that the word campanology comes, that is the art of bell ringing.

Over the three thousand from the first surviving example bells have changed and developed to those we know today. Bells are made of an alloy of ca. 22% tin and 78% copper, pretty much the same as in the first. All the same there has been much experimentation in shape and form. The bell gained its present shape towards the end of the fifteenth century and is known as the harmonious bell. It was bell-caster Gerhard van Wou who is the man behind this bell profile. Many of his bells have survived to this day. The biggest of them all is the Gloriosa bell, which hangs in the Maria church in Erfurt. It weighs about eleven tonnes and was cast in 1492.

That special sound As the clapper strikes the bell rim, you hear not only a single note but also a whole arsenal of notes. And it is this which is called the natural tone scale or partial tone scale. The first note you hear is the strike note and the under octave. Then the over octave, the minor third, major third and then the over octave, after which the notes come closer and closer until it is almost impossible for the human ear to separate them. It is the combination of these notes that gives the bells their characteristic sound. How these notes come and how strong and pure they are depends on the alloy used and on the bell’s profile. At the beginning of the seventeenth century the brothers François and Pieter Hemony from Lotharingen in the Netherlands discovered that the bells could be tuned. They milled metal from the inside of the lid in such a way that the various overtones had the right pitch. Today bells are tuned in pretty much the same way as that used by the Hemnoy brothers four hundred years ago.

Bell ringing in this country has an almost thousand year unbroken tradition. It is a tradition we should be proud of. The art of bell ringing has been transmitted in the old manner, from master to apprentice. Good bell ringing is not learned overnight. It is not as simple as pulling the bell rope and hoping to get a sound. Long practice is required to get the right result. To get them to ring at the correct tempo, to get the strike to be so hard that it can be heard far off while the sound is as soft and fine as possible. If it is hard to ring one bell it is even harder to ring a peal of two or more. But that is more fun. Fun when you get good tonal effects between the notes of the bells and a good rhythm. It is not seldom that the bells of Aurdal have summoned the congregation to church on a Sunday to the rhythm of the folk dance called springar. To achieve this the bells must be rung in the old way, by hand.

Fiddler Ola from Hamrisbrøto was also bell ringer at Slidre church. Once he painted a tar cross in one of the rafters of the bell tower there. That showed how high he wanted the bells to swing. The cross can still be seen today and by some is called “ the fiddler’s cross”. Fiddler and folklorist Olav Moe has written the following about Ola from Hamrisbrøto: “ In his old age Ola was sexton at Slidre church and when the splendid bells did not chime with the harmony he expected, you could see a grimace twist his face. It was his sensitive musician’s soul that was offended.”

Bells in the church tower, the bell tower or glockenspiel Today there are many ways to hang bells – in a church tower, in a separate bell tower or campanile, or in a glockenspiel.

The first and oldest bells we know of were mainly used as signals. Then when the church adopted them they were used to summon people to church. It was preferably smaller bells that those whose duty it was to summon the congregation brought with them. Gradually the bells used became bigger, heavier and thus harder to transport. Separate towers were built specially to hang the bells. Later church towers were constructed for the same purpose. In Valdres we have both church towers and campaniles, known as “stupul” locally.

Glockenspiel became a symbol of affluence, particularly in the towns of Flanders that experienced a boom in commerce and industry in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. There are getting on for 600 concert glockenspiels around the world, nine of them in Norway. To merit the title concert glockenspiel at least twenty-five bells (two octaves) connected to a keyboard are required.

Bell tunes As mentioned earlier, church bells exerted a strange power over folk’s minds in the old days. As soon as they heard them chime, they stopped work, took off their caps and listened. Their ringing could even turn all kinds of trolls in hills and hammers(?) to stone.

When the first churches were built in Valdres from the year 1000 on, they represented something quite new and alien to the local people. The churches were bigger than any other buildings they had seen before. They were richly decorated with carvings and paintings, pictures of angels and gold-leafed Madonnas. And above all these enormous church buildings had bells that rang loudly and in a sinister manner. Often they had not just one but several bells. When these chimed simultaneously, it was not hard to understand why the local people were solemn and respectful.

The mass celebrated then was in Latin, which was incomprehensible for most. They understood nothing of the hymns but learned the melodies and made up new lyrics to them. Similarly, the sounds and simple melodies of the bells inspired people to make up new melodies, in Valdres known as “klokkelåttar” (bell tunes). People took these tunes and hymns home with them for private use for prayers and devotions, for comfort in times of trial and tribulation. Even if these little “bell tunes” came in time to have quite profane lyrics, they retained at least some touch of Christianity.

These bell tunes seldom or almost never have any church or Christian element in them. Usually, they take their words and phrases from everyday speech. At other times they have anecdotes attached to them or are onomatopoeic: e.g. ding dang. Dalang…. Sometimes they raise an admonishing finger. As previously mentioned, many thought the bells were God’s voice. So it was not strange that God himself spoke to urge the people to live right. The Slidre church bells have a nagging tendency to chide latecomers to the service: “Late come those from Skjel, late come those from Beito” (Skjel and Beito are two districts in Øystre Slidre which formerly was attached to Slidre church). Once when one of the church bells was stolen, the other bells rang to wake and warn the vicar. The bells told him who the thieves were, where the bell could be found and, finally, where the thieves were. “Kome nord”(Come north), a bell tune from Vang might be the only one of our bell tunes to have some slight touch of Christianity in it. The bells chime:”fara varleg, vandra sparleg. Vegen er så farleg” (travel carefully, wander cautiously, the road is so dangerous). Might this relate to Ecclesiastes (chapter 5, verse 1):”Keep thy foot when thou goest to the house of God.” (King James Bible, 1611)

Why are there so many bell tunes in Valdres? The bell tune tradition is only found in Valdres. It is hard to say why this is so. Nonetheless I hazard a couple of suggestions.

In Valdres today we have 30 plus churches and rather more than sixty church bells. In the Middle Ages the number of churches was about the same but there were far more bells. Each church had from two to six bells. With so many bells ringing at all hours everywhere Valdres must have eternally echoed with the chimes. So perhaps it is not so strange we have as many bell tunes as we have.

The shape of the valley with the lakes/river at the bottom of the valley and the mountains on either side might have some influence on the sound of the bells. When Lomen got its new church just after the turn of the last century, it was decided to move the bells from the old bell tower to a new one further north and lower down in the valley. The bells were moved but their sound was not as fine as in the old location. Some years later when the congregation could afford new bells, the old ones were removed back to their old place, where they sang more beautifully than ever before. It was then thought that it was Lomis Rock right behind the church that created the right “atmosphere” for the bells. Might we then conclude that Valdres is created for church bells?

Bells echoing from distant times For a thousand years the bells have summoned us to church in sorrow and in joy. They will certainly continue to ring for generations after us. In the same way as many of the almost thousand-year-old Valdres bells rang for those who heard them when new, have they rung for the generations after and ring for us today. So one can say that the church bells do not just ring for those who find their way to church this Sunday but also ring for all, whether they are at home, working in the garden or in the fields or taking a Sunday stroll. They ring for those who have wandered here before us and who now lie in the churchyard.

Henning Andersen Growing up next door, I have developed a close relationship to Aurdal church. As a ten to twelve year-old I was allowed to help the sexton ring the bells. It was a great experience. Some years later when the sexton finished, I was quick in applying for the job. So, since 1993 I have been sexton and bell ringer in Aurdal church.

During the winter of 2004 I began studying to be a bell ringer at Løgum Convent Church Music School in Denmark, the only sexton and bell ringer in Norway to take such a study.

I have always had a great interest in folk music, something I can thank my grandparents for. I have mostly learned to play the Harding fiddle from Trygve Bolstad, but have had Harald Røine, Geir Harald Fodnes, Olav Jørgen Hegge and Håkon Asheim as important teachers and instructors.

I must to confess to having played about with the Norwegian zither and singing, thanks to Marit Mattisgard, a musical model and idol for me over many years. I have also been fortunate enough to get her to sing and play on this CD. On a pair of tracks I have played willow flute. Otherwise church organ is one of my passions.

In 2003 when Hamar diocese celebrated its 850th anniversary I was responsible for the music to a project called “Missa Valdriensis – a church service in the Valdres manner “, which was Valdres’s contribution to the celebrations. In the same year I was involved in a work ordered for the Jørn Hilme folk music festival, “Sky and Sea”. In addition I have been an active folk musician at concerts and dances at home and abroad.

The tracks The devil in the church tower Once after playing in a wedding, fiddler Jørn Hilme (1778-1854) was walking past Ulnes church early in the morning when he thought he heard someone whistle in the tower. He stopped to listen and learned the tune he heard. It is known under several names in Valdres today, but “The Ugly one (Devil) in the tower” is the title we have chosen to use here. I mostly use the Andris Dahle version but have added and subtracted bits here and there. The recording was made in Aurdal church tower autumn 2005. The oldest of the bells we hear on this track was cast by Iohan Nicolaus Derck in Horn in the Netherlands in 1752 and the smallest by Olsen Nauen bell caster in Tønsberg in 1927.

Tøstein Langbein Tøstein Langbein, Guro Ljoseng, Berit I Gladbakke lay in a snowdrift This is a ”stev”. A “stev” is a short, originally improvised piece. Transcribed by Hartvig Lassen, it was played on a Norwegian zither, a folk instrument with one melody string and several accompanying drone strings, and known as “Langeberglåtten”(Long Ridge tune). Marit got it from Begljot Hedda Lunde. Here it is played freely on a willow flute (another folk instrument), Jew’s harp and Norwegian zither.

Sylkegulen hass Bendik I Nø’en In 1891 and 1892 the Swede Einar Øvergaard visited Aurdal. He transcribed 50 tunes after Aurdal fiddler Ulrik I Jensestogon (1850-1919). About this tune Øvergaard writes:” People in Valdres think yellow silk is the top of soft elegance. It for these qualities the tune has got its name.” A fine shiny yellow horse belonging to a Bendik from Jens’s cottage is accredited with the origin of the title. Ottar Sørum made the fiddle I play here, Ulrik’s brother’s son. When Ulrik got the fiddle in 1910, he is said to have exclaimed:” If only I had had such a fiddle when I was young!”

Store Salmen The version I play here is principally after Torleiv Bolstad (1915-1979). But I have heard others play it and added and subtracted bits, as I felt fitted. This is a tune that is never the same twice in a row. Nobody can say why it is called “The big hymn”. Maybe it is due to the solemnity of the piece.

Komme nord A bell tune from Vang church after Marit Kulturstad. Probably from the old bells of the stave church now in Karpach in Poland. The bells are gone but their memory lingers on in this recording. “Come north as you did last year. Come north to church. Travel carefully, wander cautiously, the road is so dangerous.”

Hestebjøøutn I svartedauen “Horse bells during the Black Death” is most probably a variant on the better-known “Bjølllåtten” (Bell tune). But then it is a question of which came first, the chicken or the egg. I have this from a transcription after Andreas Hauge, one of Ulrik i Jensestogon’s pupils. You can hear the bells on the horse’s collar as it pulls the cart loaded with corpses during the Black Death. At the end you can hear the bells from the bell tower of Hedalen church. The oldest and highest pitched bell is a medieval Gothic bell. It is inscribed ”Nicolaus Angelus me fecit” (Nicolaus the Englishman made me), and was probably cast some time after 1200. The biggest and lowest pitched bell was cast by Matias Skiøberg in Vardal in 1822.

Klokkereisa (Bell journey) Here we have made a potpourri of several bell tunes and made a little journey out of them. We start with Skrautvoll church bells singing:”Ding-dang-dalang, Torstein Langbein, Guro Lyseng”. Then we move over to Hegge church where we have two variants:”Long way for those from Beito, late come those from Skjel” after Thore H.Molorhaugen and Guri Molorhaugen. After which to the Slidre bells (transcribed by Hartvig Lassen), then Volbu (after Thore H.Sebuødegaardseje), a quick visit back to Slidre before ending in Røn church. Both the latter are after Thore H.Sebuødegaardseje.

Hedalsklokkelåten This tune has a long history behind it. Ever since I learned St. Tomasklukkelåtten in 1988, I have had the idea that Hedal church should have one too. However, the final version was not ready until spring 2006. Since my mother’s family comes from Hedalen that church and its bells have meant something special to me. There are many legends and stories linked to that church and its bells. One of these that has been the inspiration for this bell tune. The lyrics I have picked for it are: ”Ding-dang-dalang, ding-dang-dalang, you won’t find the like except in Trondheim.” The point is that the bells are right. In Hedal tower hangs a small bell inscribed:”Fecit Amstelodami Anno 1718.” The name of the caster is not given. However, if we compare the bell profile and the spelling of the name “Amstelodami” with the bells that hang in Our Lady’s church in Trondheim, we will soon conclude that they have been cast by the same man. Then it is likely that the famous Dutch bell caster Jan Albert de Grave cast the little bell in the tower in Hedalen.

The Black Death left almost all of Hedalen depopulated and abandoned. The church fell into decay and the forest grew. Once a hunter from Hallingdal came. He shot at a bird but his arrow hit the church bell making it ring. Believing it was a hulder church, the hunter through his steel for striking sparks from flints over the church tower to drive out the evil spirits. Only then did he dare enter the church. There in the dark he saw a bear lying in front of the altar. The hunter shot the bear and flayed it there and then. That is why even today there is a bearskin in a glass frame in the sacristy. And on the spot where the steel fell is a farm called Ildjarnstad (Fire Iron Place to translate literally).

A hulder by the way is a kind of fairy woman, human size and shape but with a cow’s tail, that lures men to their destruction.

Another legend tells how one of the church bells should be transported to Bagn church. This was in winter so the bell was placed on a sledge, which was drawn up the hillside to the Berge farm. From there the journey was to go over Bærskinn (Mountain tarn) and further up the valley to Bagn. But when sledge reached the middle of the tarn, the ice broke and the bell sank. That is why one can hear the bell now hanging in the tower singing: ”My sister lies in mountain and water, my mate lies in Lake Mjøsa.”

Vårduft (Scent of spring) This tune can be found in several variants in Valdres. On this CD I mainly use a transcription after Olav Moe (1872-1969), originally from Vestre Slidre but living in Aurdal for most of his life. Living up to its name, the tune is full of birdsong, burbling brooks, buzzing flies and the scent of bird cherry and lilac.

Thomasklukkelaatten Played on the Norwegian zither here, this is one of the best-known Harding fiddle tunes found in numerous variants. A Harding fiddle is a Norwegian folk instrument, differing from an ordinary fiddle not just in being richly decorated but also in having a set of under strings that provide a drone. This free zither version is after a transcription L.M. Lindeman made after Berit på Pynte in 1848.

Slidreklukkelaatten In the Middle Ages Slidre church in Vestre Slidre had twelve bells. Now there are only six. Two big ones hang in the bell tower while four smaller ones, all from 1100.1300, still hang in the church tower. We have a whole repertoire of tunes belonging to the bells in the bell and church tower. On this track we have put two bell stev after Gullik Kirkevoll together with the fiddle tune. “ My sister lies in Saltmannsbøta and the thieves sleep at Dinglo” and “ My younger sister hangs in the closet, she’s made of Halling silver, in Mosegjeld suddenly one dark autumn night while the streams roared and the moon was black. Of the silver she got such a strange power.”

The Jew’s harp plays a Thomasklukke variant after Olav Hauge while the four bells of the church tower play freely.

Likferdssalmen åt Joma (funeral hymn for Joma) This tune has its name from a man from the Jome farm in Vestre Slidre. He was called Joma or Jomin. He lost his wife, and though he was not the most eloquent of men, he could sing. So at the edge of the grave he sang this last farewell to her:” All the love I bore you, yes, it was fourteen years and fifteen days, but now it has run out in evensong, sudlium dudium dadi deia…..!”

I Oletjedn, I Olekinn The tune is about a milkmaid on a mountain farm by Ole Lake. She was picking berries. Her little boy who was with her suddenly disappeared. She went and searched and called for him but the boy did not turn up. She sent for folk and they took one of the bells from Hegge church with them to Ole Lake. They rang the bell for three days. All at once a door opened in the mountainside and the boy appeared. But then the rope holding the bell snapped, the door shut and the lad stayed in the mountain. This melody has many of the same themes and motifs as the Thomasklukkelåtten. It has also been used in classical music, for instance by Grieg’s. Marit has this traditional tune after Anne Fuglesteg and Ingvar Hegge and several others.

St. Tomasklukkelåtten On Filefjell, the mountain between Sogn and Valdres, stood the old St.Tomas Church. It was a stave church probably built around 1200. A mass was held here each year at the beginning of July to which flocked folk from Valdres, Hallingdal and Sogn. In all of southern Norway the church was reputed to have healing powers. Unfortunately, many came to drink and have fun. So as well as the church service there was often carousing and brawling that could even end in death. Afterwards it was said:” There many a vigorous fellow got a beating, many a horse ridden to death and many a maid raped”. (It is more concise and rhymes in the original Norwegian!)

Outraged by this unruly behaviour, the bishop ordered the church to be pulled down. Demolition work began in 1808. When the bells were taken down, it was decided to transport them to Øye church further south in Vang. The transport was to take place in winter after Smedalsvatnet, a lake, had iced over. The two bells were each mounted on a sledge and dragged over the ice. Once they had got to the middle, they left the sledges and went home to rest. On returning the day after, they saw that the ice had given way under one of the sledges taking the bell with it into the depths. The remaining bell was dragged to Øye and hung there. But when they rang the bell, they could hear from afar the echo of its sister in Smedalsvatnet.

Now a new church stands on Filefjell and the bell from the old church has returned to ring out over the mountain farms between Sogn and Valdres as it has done since the thirteenth century.

Hedalsklokkene In Valdres there has long been a tradition of hanging church bells both in the church tower and in a separate bell tower. An example of this is Hedalen. On this track we hear all four bells, both the two in the bell tower written about earlier and the two smaller ones in the church tower, an English one from the end of the twelfth century and the Dutch one cast in 1718.